Memory, music, and the politics of Basant across the Radcliffe Line

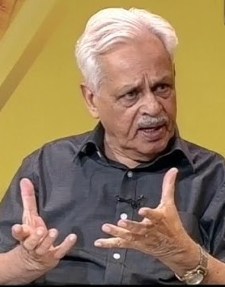

TWNETY-ONE YEARS years ago, while walking the streets of Lahore, I had this funny idea: ‘let’s see how the Lahore skyline looks like?’ Gobind Thukral, a veteran journalist senior to me by decades, liked the idea, and both of us climbed atop a tall commercial building, with a rather bewildered friend from Dawn newspaper following us all the way up.

As I looked around mesmerised, soaking it all in, and our friend from Dawn pointed out various landmarks, Thukral pointed to the hundreds of kites dotting the sky and said, “Mulliyan ne kise din bandh karva deni hai eh patangbazi!”

I looked at him, askance. “Dekh laina,” he said, and never bothered to explicate.

Next day, I asked Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi, then the Chief Minister of East Punjab, if there was any plan to ban kite flying. He laughed at the ridiculousness of the question, said, “Patang to bina Basant nahi, Basant to bina Lahore nahi,” and then let out a loud guffaw. He wasn’t done.

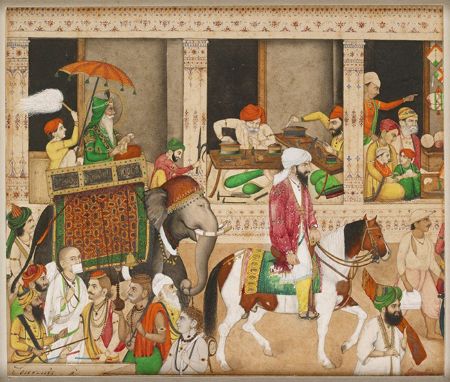

Maharaja Ranjit Singh in a Lahore bazaar, from a historic miniature painting

“Why are you asking, Sardar Sahib? Basant and kites are a gift of Maharaja Ranjit Singh to Lahore. Why do you want it banned?” I just laughed a little sheepishly and looked sideways at Thukral, who sat expressionless. He was sitting at a separate table with Punjab’s Chief Secretary Jai Singh Gill and Minister Surinder Singla. The two also joined in the laughter. Part of me regretted asking the question, and I never included either my query or Elahi’s answer in the news report I filed for the English daily that I worked for.

That was 2004.

Next year, Pakistan banned Basant Panchami in Lahore, and soon the ban covered all of Punjab. The Supreme Court of Pakistan had taken the lead in this mullah-backed move, citing some fatalities caused by the sharp crystallised glass-laced string. I called Thukral and asked him how he could predict the end of Basant in Lahore with such certainty.

“I could see the Afghan mullah thought process penetrating the Punjabi right wing in Pakistan. You can’t miss the Afghan Taliban influence on Jamaat-e-Islami or Jamaat-ud-Dawah. Basant comes handy for any killjoy and can always be painted as a Hindu influence. Even a dimwit Taliban would have figured it out if he had climbed that high-rise building with us and had looked at the sky that day,” Thukral explained patiently.

Journalist friends in Pakistan told me kites continued to be a rage in Kasur, Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, even Peshawar, for some more time, but then the mullahs hardened their stance, the Sharifs turned into Zia in some ways to keep the hardcore happy, and rarely did a braveheart stand up for Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s gift.

Salman Taseer

Salman Taseer did. As Governor of Punjab, he declared in 2010 that he would celebrate Basant, consequences be damned. In response, Senator Pervez Rashid of the PML-N said he would personally drag Salman out of the Governor’s House and lynch him.

Thukral called me and said I should do a TV programme on “cultural commons”. I was perplexed, since the timing did not seem right.

India-Pakistan relations were witnessing a cautious, hesitant thaw after months of diplomatic freeze following the 2008 Mumbai attacks, and there was talk in the air about the possibility of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh meeting his Pakistan counterpart Yousuf Raza Gilani in Thimphu, Bhutan, in April.

“We need to change the ‘mahaul’. People like Salman Taseer need backing. Let us talk about Basant and shared culture, shared history, and shared pain. Do a programme. I will be there.” Thukral could be very convincing. I used to anchor a panel discussion programme on a vernacular TV channel, and he sure was there for the episode.

While I kept harping about the deep mistrust over terrorism, the Kashmir dispute, the perpetrators of the Mumbai attacks, and Pakistan’s insistence on resumption of a comprehensive dialogue covering all issues, Thukral kept up the importance of cultural commonalities.

“You cannot keep the same people divided socially. Politically, they can be in two separate countries, but socially, they will always inhabit the same milieu. These are the twins joined at the hip by Lohri and Basant, and you want to divide them with Eid, Holi and Diwali?” Thukral was a prime example of a hardcore secular Punjabi Hindu devoted to his land’s rich heritage.

Salman Taseer, who had dared to celebrate Basant in 2010 in defiance of the mullahs, was assassinated the next year, shot 27 times with an AK-47 rifle. The assassin was celebrated across Pakistan even before Taseer could be buried. When the killer was executed, an estimated 30,000 attended his funeral, chanting slogans the likes of which gladden the hearts of Taliban anywhere.

Gobind Thukral

“Do a programme,” Thukral told me. He was duly on the panel, talking about the Pakistani Christian woman Aasiya Bibi, who had been convicted of blasphemy. Taseer was killed for advocating her cause. Thukral warned that if we in India did not stand against such mullah mindset, we would soon start mirroring it, and would have crowds asking for similar blasphemy laws, and a similar public passion-whipping would masquerade as politics.

Years passed. Politics in India took a decisively saffron turn, and Punjab saw much talk of blasphemy laws. Aasiya Bibi was smuggled out of Pakistan in the summer of 2019, and Thukral was on the phone: “Do a programme.” But he wasn’t available. Cancer had gotten to him, but he worried about the country, about Punjab, about journalism, till the very last breath.

“Write in Punjabi, too,” he would goad me, telling me that he felt happier with his column in Ajit newspaper than his work in English. “We need to talk to our people in their language.” I took his advice. “And never stop talking about Punjab – the real Punjab. Lahore is the thing, not Chandigarh,” he said, taking my hand in both his frail hands as we sat on the first floor of his Panchkula residence. I promised.

In the September of 2019, Gobind Thukral passed away. I often miss him for his perceptive reading of political events, cultural phenomena and geo-strategic games. His book on the media’s symbiotic relationship with violence, ethnic violence and war keeps him alive for me. His lovingly scribbled “With much love, for Sukhvinder” reminds me of that promise. No one other than my mum calls me that. And Thukral Sahib did, of course.

There is a reason I am reminded of Gobind Thukral at this time of the year, and it has to do with Basant.

Pakistani regimes kept buckling before the edicts of their moral police, and one by one, simple pleasures were legislated away, Basant being one of them. Pakistani mullahs indulged in an annual ritual chorus about this being a festival with Hindu origins and thus somehow un-Islamic, just as the ayatollahs in Iran had tried to put a damper on Nowruz festivities. But while the Iranian clergy quickly realised the futility of trying to kill off an ancient tradition deeply rooted in Iranian culture and history, the Pakistan clerics remained more influenced by Afghanistan’s Taliban. And various power structures in Islamabad and Lahore could not defy the powerful maulanas.

But this year, Lahore is all set to see kites flying high in the sky. Thukral would have loved it. “Do a programme, Sukhvinder,” I can hear him saying.

Maryam Nawaz is hardly a democratically elected Chief Minister of Pakistani Punjab, just as her uncle Shahbaz Sharif is an illegitimate Prime Minister of the country, but between the two of them, they have now promised to restore Lahore’s cultural heartbeat by celebrating Basant and removing the ban on kite flying.

Lahore’s cultural heartbeat — rooftops, music, and collective celebration.

There is an excitement in the air.

“The deserted rooftops of Lahore will once again be floodlit, crowded, and lively. Once again, there’ll be nostalgic songs playing and blaring, the wafting scent of barbecue and the jubilant shouts of ‘bo ka ta’ will fill the open spaces of Lahore,” Hamza Malick’s piece this past weekend in The Friday Times of Pakistan reeked of exhilaration almost at the same level as Rose Sayer’s (Katharine Hepburn) words to Charlie Allnut (Humphrey Bogart) in the 1951 film The African Queen: “I never dreamed that any mere physical experience could be so stimulating!”

For a country whose 60 per cent population is under 30, a 20-year-long ban on kite flying might have resulted in a huge loss of skill in this artistic department of flying kites and cutting off others’, and even more significantly, being happy in the loss of that beloved colourful but fragile flying object in the sky.

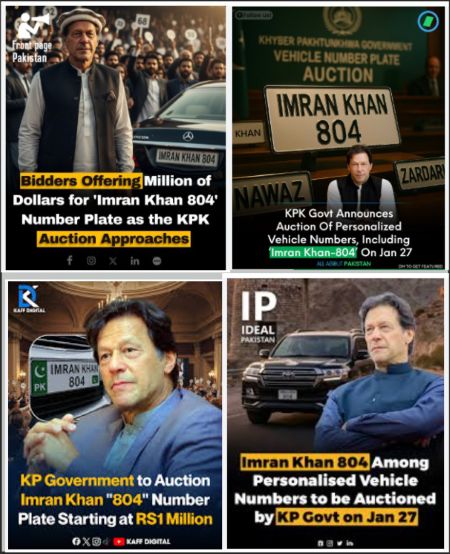

But Pakistan is a country that breathes politics in its streets. The country’s most popular leader is in jail, and 804 is the most sought-after number, so rare to come by that Pakistan’s vehicle registration authorities no longer issue that number for any bike, car or truck. Imran Khan is a pariah for the country’s powerful army and its puppet civil front, the Shahbaz Sharif government.

Imran Khan

The world has not seen Imran Khan even once since his arrest on 9 May 2023. No TV channel can telecast his picture or even a video clip from yore showing Imran Khan, and for a long time, just uttering his name was enough to invite punitive action. His party, Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaaf, though not banned, has been effectively decapitated, its leadership either arrested or in hiding, and a bunch of lawyers currently at the helm are routinely hounded and incapacitated in myriad ways by the army-backed regime.

And still Pakistani Punjabis are all looking forward to Basant. A very, very limited Basant, one that comes with time bars, QR codes and regulated kite sizes.

Thousands of PTI workers were planning to fly kites this Basant with Imran Khan’s picture, or Qaidi Number 804 printed on the kites, but Pakistani journalists are now reporting that police teams have fanned out in Lahore and other cities, telling kite makers that any kite found with Khan’s picture or the numerals 804 will put them out of business.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government auctioned ‘804’ number plates since Imran Khan’s party is in power in that state.

Imran Khan’s die-hard fans, who otherwise refrain from coming out on the roads because the regime rarely thinks twice before firing directly into crowds – something it has done repeatedly – are now busy preparing stickers. The big political plan is to slap these stickers of Imran Khan’s face and “804” on any kites they could get hold of, and let these fly and spread the political message of resistance.

Basant is nothing if not a declaration of the freedom of the human spirit, and Lahore is set to witness this cultural commonality in the second week of February.

Hamza Malick talked of scenes of yore – “the floodlit night, shouts from the neighbourhood … a rhythm that’s lively, joyous, and antidote to stress” – but the Maryam Nawaz government is alive to what can actually cause it much stress. In fact, serious distress.

And it is a popular song — Nak Da Koka!

Her government has come up with a “Theatre Performance Policy 2025”, and has ostensibly banned 132 Punjabi songs because it perceived these as “immoral, obscene and with double-meaning content,” but the real reason is that these days, a lot of stuff in Pakistan has “double meaning” and could be politically explosive, much like “Achhe Din” in India carries a double meaning now, as do “Vikas” and “suit-boot”.

“Koka nak da dhe peya ae

Jaddan da tu turreya aen

Palle kakh vi na reh geya ae”

Sargodha’s Malkoo is Pakistan’s top pop star, and while he has sung and performed hundreds of bhangra and folk items, and composed dozens of songs, it is Nak Da Koka that has made him a star and created immense difficulty for him.

The utterly harmless Nak Da Koka has just one single line – Jail Adiala, qaidi ath so chaar (804) howay, oya dagha dende jinna naal dher pyar howay – and it has the potential to send the song reverberating through the Lahore air this Basant. Already, it has crossed 100 million views on YouTube, and continues to be a rage.

Malkoo, whose song “Nak Da Koka” became an unexpected anthem of defiance

Malkoo faced much legal scrutiny for the song, was arrested, and was then forced to refute his own arrest in late 2023. “Actually, it was meant to help me manage the crowd,” he said, his words a classic “double meaning” Orwellian move that Pakistanis have become familiar with now. Qawwal Faraz Khan thought it fit to sing this Malkoo song at a Lahore government event, and was arrested.

Faraz Khan faced serious charges, including sedition under Sections 505 and 504 of the Pakistan Penal Code, but then Malkoo came up with Qaidi No. 804, a song completely devoted to Imran Khan.

Qaidi 804 vay, kadi vi na mun da har ay

Asan vote Khan nou pannaw ay

Kaptan apna nou asan jittanan ay

Sanu Khan day nal pyar ay

Now, Malkoo’s songs are among the 132 banned ones, and Lahore is looking forward to singing the songs of resistance this Basant. As Pete Seeger, from whose “We Shall Overcome” we derived “Hum Honge Kamyaab”, used to say: “Songs are funny things. They can slip across borders. Proliferate in prisons. Penetrate hard shells.”

Well, Pakistan has some songs coming. Unfortunately, we are not contributing any, despite being a huge powerhouse of musical soft power. Recall Pete Seeger’s words: “A good song reminds us what we’re fighting for… I always believed that the right song at the right moment could change history.” Those who know the history of Pagri Sambhal Jatta would know this too well. Malkoo’s voice will define the sound of Basant.

Maryam Nawaz, who has promised to revive Basant while tightly regulating it

Maryam Nawaz is all set to bring back the spirit of joie de vivre to Lahore, and Lahore is all set to play Malkoo’s songs at top volume. Police in eastern Punjab are all set to scour the skies for any kite displaying the picture of a 73-year-old prisoner or anything – a kite, a T-shirt, a vehicle, or a dog – branded with the digits 804.

All kite-flying associations, manufacturers, traders and sellers of kites are being registered with the relevant Deputy Commissioner of the district, and all kites have to carry seller and manufacturer QR codes. Various ordinances to this effect have been issued. Kites can be sold only from February 1st to 8th, and after that, selling and flying kites will be prohibited outright.

“So serious is the Basant-loving government of the Sharifs that when it found out what was meant by an algebraic expression that popped up as a display picture on many social media accounts – 282+42+22 – it sought to get it removed,” said a podcaster from Pakistan. He jokingly said that if anyone in the government were any better at maths, the regime could have even notified a ban on all composite numbers that could be a sum of three squares in four ways.

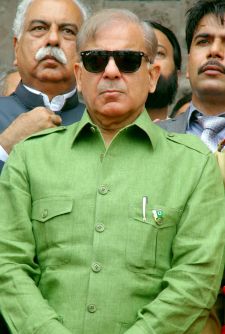

Shehbaz Sharif

In 2017, before Imran Khan’s surge threw the Sharifs off their rocker, Shahbaz Sharif, then Chief Minister of Punjab, had tweeted: “Complete BAN on Basant… No one can be allowed to play with the lives of ppl… concerned DPO will be responsible for any violation of ban.”

Basant was painted as a “throat-cutting kite-flying Hindu festival”.

Now, Sharifs of all generations are discovering the spirit of Basant, but are afraid of what it might unleash. Pakistan is right next door, and Lahore is virtually a stone’s throw away. In fact, literally so, if I had a good slingshot and an idea to fire. But we remain oblivious to what’s happening in the city that we raise to subliminal level in our idioms: Jis Lahore Nahi Vekhiya, Uh…

One of Pakistan’s leading human rights lawyers and activists, Imaan Mazari, and her equally strong-willed human rights activist husband Hadi Ali Chattha, were hounded all of last week, with a puppet judge of the regime ordering the police to arrest them within hours, and top lawyers sheltering the couple inside the premises of a high court for three days and two nights.

Police take human rights activist Imaan Mazari to court in Islamabad, August 2023. Courtesy: Ghulam Rasool.

As thousands of cops laid siege to the high court premises, all of this high drama played out in full public view, even as the Pakistani Punjab government advertised plans to revive Basant and paint itself liberal. Unfortunately, it did not make much news in India, and I could not find anyone ready with facts and background to talk about it in a TV programme.

I missed Gobind Thukral. Did you hear “Do a programme, Sukhvinder”? Am I suffering from auditory hallucination affliction in this season of Basant?

In a hybrid democracy, an army-backed government cannot handle a stubborn 30-year-old woman determined to fight for justice for the most victimised, and is afraid of a jailed septuagenarian’s face peering down from a kite hundreds of feet in the sky – a mirror image of a strong government under a strong leader on this side of the Radcliffe Line, unable to handle a PhD scholar talking of justice without holding him behind bars for five years and more, and calling his ilk the tukre-tukre gang. It’s a direct line Gobind Thukral would have been unafraid of drawing, and he would have goaded me to have that discussion.

A lot has been happening in what was a part of India, and much is happening in what was a part of Punjab, and still is.

As Thukral would have said, we are joined at the hip – by five rivers, by Lohri, by Basant, by a thousand songs, by a million stories, by scores of invaders, by Dulla Bhattis and Gama Pehalwans, by Singh Sabhas of Lahore and Amritsar, by memories of Shaheed Bhagat Singh’s Lahore and of Preetlari at 5, Nisbat Road, a spot that Gobind Thukral had pointed out to me with much poignancy. But we aren’t paying much attention to what’s happening in Pakistan.

Fact is, we aren’t even bothered by how the lakh and a half plus population of Nankana Sahib lives, and whether the couple of thousand Sikh residents of this town enjoy a relationship of solidarity with a couple of thousand Christian residents. This, when we yearn for Nankana Sahib every day, morning and evening!

A protester amid tear gas, reflecting rising public anger against Pakistan’s power structures

Fact is that there’s a wave of resistance simmering in Pakistan; there’s much public anger against the army and the army-backed puppet regime; and there’s much fervour for haqiqi democracy, haqiqi azaadi – slogans that the Sharifs and Asim Munir abhor in equal measure. Common people are no longer interested in India-bashing, and Pakistani Punjab and many Pakistani scholars are questioning some fundamental issues and positions regarding Partition and India.

It’s time we start peeping into our neighbour’s house. Our government has made that difficult by banning many newspapers and TV channels following the Pahalgam attack, but we should ask ourselves if that is helping us in any way. Popular talk in Pakistan is imbued with references to Inquilab against the entrenched regime.

Basant in Lahore — a festival of rooftops, rivalry, and release.

The Deobandi-Wahabi-Salafi mullahs are forced to gulp their opposition to kites and music, and Lahore is set to see a skyline dotted with paper squares tied to strings. Imagine how many 20-year-olds will see such a skyline for the first time in their lives?

Basant will be back in Lahore. We should also have more Gobind Thukrals. Journalists like him and festivals like Basant are invariably irreplaceable!

RIP, my friend and guide, and happy Basant. The likes of you were the Basant of journalism in this region. If only you knew what all I remember from our conversations about our neighbour, including these lines that I once recited for you and, in my innocence, said, “Malika Pukhraj ki lines hain…” and you had cut me off, saying, “Oye Sukhvinder, ki ho gaya tainoo? Hafiz Jalandhari diyan lines ne, Sukhvinder!”

नहीं कुछ भी याद, यूँही बा-मुराद, यूँही शाद शाद…

डोर और पतंग देखो, लड़कों की जंग देखो…

कहीं दिल में दर्द, कहीं आह-ए-सर्द

कहीं रंग-ए-ज़र्द, है यूँ भी और यूँ भी

मस्ती भी जोश-ए-ख़ूँ भी, है इश्क़ भी जुनूँ भी…

Every Basant will bring your memories. ![]()

_____________

Enjoy this older song by Malkoo, steeped in the spirit of Basant and kite flying:

_________

Also Read:

JAN 21 – when US Supreme Court opened billion-dollar road for the ilk of Trump in politics

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT