Why Chandigarh’s 58-year dispute is intensifying again

CHANDIGARH WAS NEVER meant to be contested territory. It was the vision of a wounded Punjab after Partition — a modern city built on Punjabi soil, funded by Punjab’s exchequer, and imagined as the state’s capital after Lahore was lost.

Yet in 1966, when the Centre carved out Haryana and Himachal, Chandigarh was made a temporary Union Territory and joint capital — an arrangement meant to last only until Haryana built its own administrative city.

Darshn Singh Pheruman

What should have been a brief transition has instead turned into a 58-year political impasse.

This dispute could have ended long ago if political promises had matched the sacrifices Punjabis made. In 1969, freedom fighter Darshan Singh Pheruman undertook a fast unto death, demanding that the Punjabi Suba commitments — including the transfer of Chandigarh — be honoured. On the 74th day, he attained martyrdom.

His sacrifice should have been the moral full stop. Instead, it has been quietly erased by leaders who continue shouting slogans for which Pheruman actually died.

Agitations, Broken Accords and Cycles of Political Hypocrisy

Among the most vocal claimants historically was the Shiromani Akali Dal. Chandigarh stood at the centre of several Akali morchas — sector-wise marches, dharnas and agitation cycles that mobilised lakhs.

Yet once in power, especially during the long SAD–BJP partnership, these fiery demands faded. No constitutional proposal was moved. No negotiation was pursued. No commitment was implemented.

The Congress reflects the same pattern. In Opposition, it condemns Delhi’s interference; in power, whether in Punjab or at the Centre, it chooses convenience over courage.

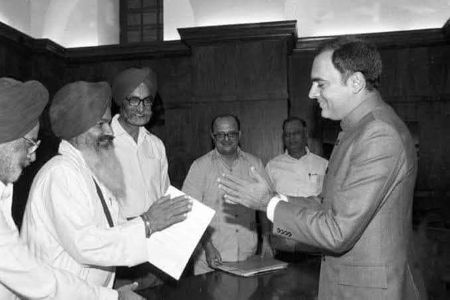

July 24, 1985 — Rajiv–Longowal Accord signed by PM Rajiv Gandhi and Akali Dal president Harchand Singh Longowal.

The most glaring example is the Rajiv–Longowal Accord of 1985, which fixed 26 January 1986 as the date for transferring Chandigarh to Punjab. A signed, written deadline — later buried without explanation.

Neither the Congress nor the Akalis displayed any intent to deliver on it.

The BJP plays both sides of the fence. Punjab BJP leaders make periodic statements supporting Punjab’s claim, but Delhi has consistently preferred centralised control over Chandigarh — including during the SAD–BJP coalition years when backing Punjab would have been easiest.

The Aam Aadmi Party is simply a new participant in an old performance. Its supremo, Arvind Kejriwal, originally from Haryana, modulates his messaging depending on geography: “Chandigarh Punjab da haq hai” in Punjab, a softer tone in Haryana, and federalist martyrdom in Delhi.

Also Read: PUNJAB BETRAYED!

His tenure as Delhi CM was marked by prolonged confrontation, controversy, and months spent in jail on corruption charges. Yet he now demands justice for Punjab without presenting a roadmap, a negotiation plan, or a workable constitutional solution.

A De Facto UT — and a Region Tired of Experiments

While politicians rehearse slogans, Chandigarh has evolved into a de facto Union Territory. It has its own police, its own bureaucracy, direct central funding, and operational autonomy from Punjab. Many residents — including Punjabis — quietly prefer UT status, fearing merger into Punjab’s overburdened civic structures. This sentiment may be politically inconvenient, but it is real and widespread.

Chandigarh Railway Station

Recent developments add to Punjab’s unease: dilution of Punjab’s representation in the Bhakra Beas Management Board (BBMB), restructuring of Panjab University’s Senate, and administrative changes in the UT.

Are these isolated administrative steps or signals of deeper federal restructuring? Is Punjab being penalised for resisting policies it considers anti-farmer, anti-federal, or anti-people?

Neither Punjab, nor Haryana, nor Chandigarh residents asked for these new tensions. All three face economic, agricultural and governance crises. Stability — not experimentation — is the urgent need.

The 2025 Article 240 Storm — A New Flashpoint in an Old Dispute

Fresh anxieties erupted in late 2025 when the Centre proposed the Constitution (131st Amendment) Bill to bring Chandigarh under Article 240 of the Constitution.

This change would empower the President to issue regulations for the UT and appoint an independent Administrator or Lieutenant Governor — replacing the current arrangement where the Punjab Governor holds additional charge.

For Punjab, this was not a minor administrative adjustment; it signalled a deliberate shift further away from Punjab’s influence over its historic capital.

Bhagwant Mann — vocal in criticism, but yet to offer a clear constitutional roadmap for resolving the Chandigarh dispute.

Punjab’s leadership, including Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann, condemned the proposal as an attempt to weaken Punjab’s rightful claim and to “snatch” Chandigarh away.

Rival parties in Punjab — despite deep differences — united in opposition, warning that the amendment would destabilise an already fragile Centre–State balance.

Following intense backlash, the Centre clarified that no bill would be introduced in the Winter Session without consultations with Punjab, Haryana and other stakeholders.

The proposal only to simplify the Central Government’s law-making process for the Union Territory of Chandigarh is still under consideration with the Central Government. No final decision has been taken on this proposal. The proposal in no way seeks to alter Chandigarh’s…

— PIB – Ministry of Home Affairs (@PIBHomeAffairs) November 23, 2025

This episode exposed a deeper truth: Chandigarh remains vulnerable to unilateral experimentation by Delhi, and federal relations remain brittle. It also stitched the past to the present — decades of broken accords and political betrayals now echoing in the constitutional manoeuvres of 2025.

The dispute is not a relic of history; it is alive, unresolved, and politically combustible even today.

Punjab Needs Statesmanship, Not Slogans

India already has a cautionary example in Andhra Pradesh, where political reversals wrecked the Amaravati capital project, devastated thousands of farmers, scared investors, and paralysed an entire state. Punjab cannot afford a similar disaster triggered by experimentation with its capital.

The Open Hand Monument — Chandigarh’s most iconic symbol of openness and modernist design.

Chandigarh needs an honest, final settlement — grounded in constitutional clarity, negotiation with Haryana, and respect for the city’s residents. Parties that demand Chandigarh for Punjab must also explain the how:

– What constitutional instrument will be used?

– What compensation formula will be offered to Haryana?

– What transition plan will protect Chandigarh’s administrative stability?

– What route will the proposal take in Parliament?

Emotionally charged slogans cannot substitute for constitutional craftsmanship.

The Centre must also abandon ambiguous notifications and half-revealed proposals. If a roadmap exists, it must be disclosed. If none exists, Delhi must stop provoking instability in an already sensitive region.

Chandigarh was built by Punjab — with vision, sacrifice and pride, as acknowledged in the 1970 announcement. What has followed is a long, bipartisan story of political betrayal.

Also Read: Punjab Gang Canal Event: BJP’s Symbolic Misstep Sparks Outrage in Punjab

Until leaders in Delhi and Chandigarh stop weaponising the city for electoral gains, Chandigarh will remain a pawn in a cynical game.

Punjab deserves truth. Chandigarh deserves clarity. And both deserve politics that finally grows up. ![]()

________

Also Read:

Anandpur Sahib Special Session — A Political Stunt in the Name of Piety

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT