A Chief Minister attacking edgewise a powerful religious cult for a “clean chit” its head issued to a corruption-accused political leader and the assertion by the dera of its moral authority has pushed Punjab to confront questions its politics, and much of its media, usually avoid.

TIMING, SYMBOLISM, MORAL AUTHORITY, and institutional silence are all threads that weave through the politics of Punjab, a state shaped as much by religious history as by electoral politics.

First, the facts that are undisputed. On 2 February 2026, Baba Gurinder Singh Dhillon, head of Dera Beas, visited Bikram Singh Majithia in New Nabha Jail. On the same day, the Supreme Court of India heard and decided Majithia’s bail application, granting him bail.

After the meeting, Gurinder Singh Dhillon publicly stated that the allegations against Majithia were “false,” but this was minutes before the apex court’s verdict.

In public life, timing is never neutral; it speaks even when intent remains silent.

It is no one’s case that the dera head knew the outcome in advance, neither is there any proof that the visit influenced the Court. Having firewalled oneself by thus defining the legal boundary of this discussion, we are now free to engage with questions any reasonable person might ask.

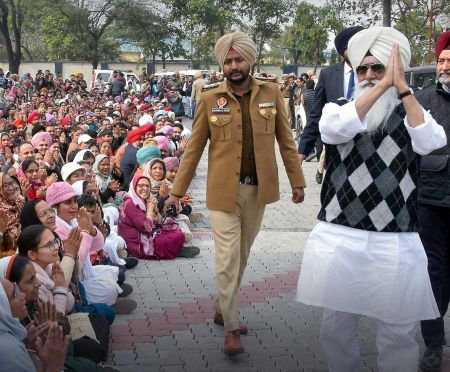

Gurinder Dhillon’s Nabha jail visit that triggered political and ethical debate.

Public conduct is judged not just by legality. A lot lies in the turf of phenomenology – an understanding of the lived experience, before it is shaped or misshaped by partisan political statements. So, the dera head is fully within his rights to meet Majithia in jail, just as he is entitled to his opinion about anyone’s guilt or absence of it.

But the unresolved question is this: why choose that very day? Bail hearings in the Supreme Court are scheduled in advance and are publicly known. Any earlier or later date would have avoided controversy altogether. Timing, in public life, is not neutral. It communicates—whether intended or not.

And any dera head who also claims to be a deeply spiritual person has an elevated sense of timing. One can reasonably assume that he knew why meeting Majithia on that day, at that very hour was important, and why it was equally important for him to come out and speak about the accused’s self-proclaimed innocence.

From Compassion to Commentary: When Moral Authority Speaks Mid-Trial

Had the visit remained private, it would likely have been read as a personal act—friendship, compassion, or solidarity. What altered its meaning was the public declaration of innocence while the matter was still sub judice. It still is.

Also, one thing that the dera head did not state, and Majithia was not expected to state, was this: the top court was not even involved with the question of Majithia’s innocence. It was only a hearing about his bail, not about the merits of the multi-crore corruption case against him.

When asked whether it was appropriate for a spiritual leader to visit an undertrial accused in a serious drugs case, Baba Gurinder Singh Dhillon responded that Majithia was a relative and a friend—and asked what was wrong with meeting a friend.

That response, rather than closing the matter, sharpened a question Punjab rarely articulates openly:

Who gets to speak with moral authority while courts are still speaking with constitutional authority, and are yet to test the matter in a crucible of investigation, evidence and justice?

Courts determine guilt or innocence. Religious leaders command faith, not adjudication. When a powerful dera head publicly dismisses allegations on the very day of a Supreme Court hearing, the act becomes politically symbolic, regardless of intent, and also partisan.

Courts determine guilt or innocence. Religious leaders command faith, not adjudication. When a powerful dera head publicly dismisses allegations on the very day of a Supreme Court hearing, the act becomes politically symbolic, regardless of intent, and also partisan.

Symbolism does not require influence to matter. It shapes public perception—especially in a society already sensitive to the idea that power, access, and outcomes may not be evenly distributed.

This is not about accusing a dera of interference. It is about recognising that words spoken from unaccountable authority carry weight without responsibility.

As it is, politics in Punjab escaped asking questions that were raised in international fora: the deep links of the pharmaceutical barons with political tsars, and the heady concoction of spirituality, pharma and big money.

This particular dera has been enjoying an almost Teflon shield, even though some high-profile devotees, namely Malvinder & Shivinder Singh of Ranbaxy fame, made news for all the wrong reasons.

Why does it become easy for power politics to avoid raising questions about data falsification, drug manufacturing violations, supply of substandard medicines globally, or having to pay USD 500 million in penalties to US regulators in 2013? Those questions never became a part of the political discourse in Punjab.

At times, one becomes convinced that having spiritual and personal connections with a powerful dera head helps in ways that remain fuzzy.

Bhagwant Mann’s Question—and Why It Disrupted the Script

What transformed this episode into a political rupture was the response of Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann.

By questioning the propriety of a religious “clean chit” during an ongoing judicial process, Mann broke a long-standing convention in Punjab politics: do not publicly question deras. Certainly, not one as powerful as the one headquartered in Beas, with its real estate interests dotting the countryside, towns and cities every few kilometres.

Whether one agrees with Mann or not, the significance lies in the question he raised, not the tone he used:

Should spiritual authority publicly validate or negate criminal allegations while judicial proceedings are underway?

This was not merely a political remark; it was an institutional question. It challenged the deliberately blurred boundary between faith and power that most governments quietly accommodate.

Was Bhagwant Mann aware that he was re-opening a fundamental question from 1st century CE, a question that has the authority of a super-human: “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”

This was a church versus the state question that Mann raised in a very pithy manner, and with his three lines, drew a conceptual distinction between political and spiritual obligations.

Triggering a storm of protest, Bhagwant Mann tweeted

ਕੱਲ੍ਹ ਬਣ ਜਾਣ ਭਾਵੇਂ ਅੱਜ ਬਣ ਜਾਣ

ਅਦਾਲਤਾਂ ਦਾ ਓਥੇ ਰੱਬ ਰਾਖਾ

ਜਿੱਥੇ ਮੁਲਾਕਾਤੀ ਹੀ ਜੱਜ ਬਣ ਜਾਣ …— Bhagwant Mann (@BhagwantMann) February 3, 2026

With a simple statement of fact-cum-opinion, he covered the debates dating to Reformation (16th century), Enlightenment (17th–18th centuries) and modernity.

The discomfort that followed within Mann’s own party was revealing. Aman Arora, president of the Punjab unit of the Aam Aadmi Party, struck a conciliatory note, emphasising respect for Baba Gurinder Singh Dhillon and describing the visit as personal. The opposition, led by Congress leader Partap Singh Bajwa, seized on the contradiction and criticised Mann.

The result was a rare moment of clarity: one Chief Minister, multiple political compulsions. Governance demanded a question; politics demanded caution.

Why Sikhs React Differently: History That Refuses to Stay Silent

This episode struck a deeper chord because Sikh history is not neutral on deras. Sikhism rejects intermediaries. The Guru Granth Sahib is the eternal Guru. That principle led to the Gurdwara Reform Movement of the 1920s and the creation of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), explicitly formed to wrest control of gurdwaras from mahants and deras that had become hereditary, unaccountable power centres.

That struggle was not symbolic; it was foundational. It shaped Sikh political consciousness and the very birth of the Shiromani Akali Dal.

Which is why every visible convergence of political power and dera authority revives an old anxiety: are parallel centres of authority quietly returning?

A past precedent that reshaped Punjab’s political memory.

The Akali Dal knows this terrain painfully well. Its past accommodation of Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh of Dera Sirsa inflicted lasting damage, alienating large sections of the Sikh community and eroding the party’s moral standing. That precedent hangs over the Majithia episode now, especially given Majithia’s proximity to the party’s leadership.

At the time, Akali Dal was a reformist movement challenging deras and mahants; now the party is navigating survival, burdened by its own contradictions.

The Gurinder Dhillon–Majithia episode exposes this transformation. Caught between defending one of its own and avoiding another rupture with Sikh sentiment, the Akali Dal appears unable to articulate a clear moral position. Silence, hesitation, and ambiguity have replaced leadership. It is in an abyss like this that political parties often commit suicide.

Also Read: A Clash of Faith and Politics

Punjab has seen the cost of such ambiguity before. When political expediency overrides doctrinal clarity, the damage is not immediate, but it is lasting. Trust erodes quietly, relevance fades gradually, and history moves on.

The Question Punjab Avoids—but Can No Longer Ignore

Strip away personalities and politics, and one question remains:

When religious authority operates in political and legal spaces without accountability, who sets the limits?

Deras are not elected. They are not subject to public scrutiny. Yet their gestures can alter political behaviour and public confidence. In such spaces, ambiguity becomes power, and corrodes trust.

The real nature of Gurinder Dhillon–Majithia ties might be difficult to prove, but the episode is important not for what can be proven, but because of what it reveals.

A Mirror Held Up to Punjab

The stance of the opposition parties, Akali Dal, the Congress or the BJP, shows how they are ready to kowtow to any vote bank, even if it means blatantly sucking up to illegitimate sources of power, money and influence.

The stance of the ruling party shows it is ready to do the same. One thing about power games and hunger games is always the same: seeker of power is ready to cannibalise the other. It is ‘Lord of the Flies’ all over again.

Punjab’s real crisis is not faith in politics, but the quiet comfort with unaccountable power.

No evidence suggests foreknowledge of a bail outcome. No evidence suggests interference. But the timing, the public endorsement, and the political unease that followed have forced Punjab to confront questions it prefers to sidestep.

This is not an allegation. It is a mirror.

It asks whether Punjab’s institutions are strong enough to withstand symbolism, whether its politics can draw clear boundaries with faith, and whether silence, once again, will be mistaken for stability.

History suggests that when these questions are ignored, the cost is paid later, in trust, credibility, and moral authority.

As they say, the ‘babas’ know everything. And as you’ve often heard, ‘Yeh public hai, sab jaanti hai’.

The problem is: only one of these is true. ![]()

__________

Also Read:

A Clash of Faith and Politics: The Akal Takht’s Bold Move and the Future of Sikh Leadership

Budget of Equality and Responsibility: Punjab Must Engage, Not Evade — Sunil Jakhar

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT