Why Shashi Tharoor’s praise of Narendra Modi’s lecture raises deeper questions about truth, history, and the health of Indian democracy.

IT CAME AS a surprise—though perhaps it should not have—that Prime Minister Narendra Modi was invited to deliver the sixth Ramnath Goenka Lecture, as if the people of India had been waiting, breathlessly, to hear him speak on journalism.

My first reaction was incredulity. What right did he have to lecture India’s journalists when, in eleven years as Prime Minister, he has not addressed even a single press conference? Journalism, after all, is grounded in accountability, in giving answers, and in facing questions—not in monologues delivered from elevated platforms with no risk of cross-examination.

But then, I reminded myself, this was not a forum for journalism. It was a forum for Narendra Modi to think aloud on topics dear to him, with no fear of contradiction. It is difficult to blame him for accepting the invitation; the question is why such an invitation was extended in the first place.

Ramnath Goenka was no ordinary media proprietor. He was a political force in his own right. Modi reminded the audience that Goenka had contested the 1971 general election from Vidisha on a Bharatiya Jana Sangh ticket.

What he did not mention was that in an earlier election, Goenka had done everything in his power to ensure V.K. Krishna Menon’s defeat from North Bombay—and then had to swallow humiliation when Menon won. That historical omission was not accidental; it was convenient.

Modi also narrated that Nanaji Deshmukh had told Goenka that he was needed in Vidisha only to file his nomination and later collect his certificate of election.

What he left out—again conveniently—was the crucial assistance of the Gwalior Rajamata, Vijaya Raje Scindia, who campaigned for him tirelessly. She, more than anyone else, helped him cross the finish line in a year when Indira Gandhi swept the country.

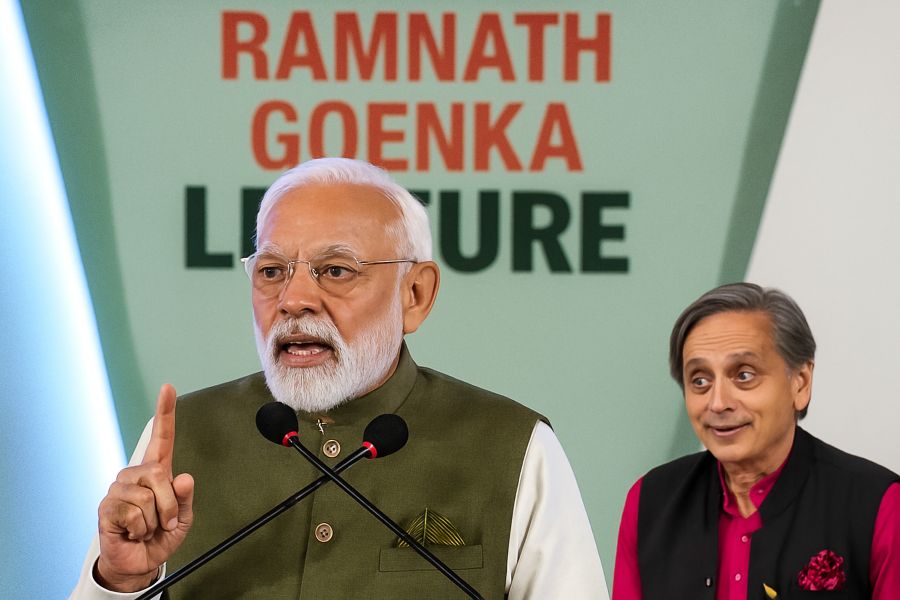

PM Narendra Modi speaking at the Ramnath Goenka Memorial Lecture

If the Prime Minister wanted to invoke history, the least he could have done was to tell it honestly.

Ordinarily, I would not have bothered listening to the speech at all. Modi is incapable of speaking on any subject without turning it into an exercise in self-glorification. I have listened to him in person only once—during the centenary of Sri Narayana Guru’s meeting with Mahatma Gandhi.

Even on that solemn occasion, when one expected reflection on one of India’s greatest reformers, he spoke mostly about his government’s achievements, his schemes, his initiatives. There was very little on the philosopher-saint who devoted his life to dismantling caste oppression.

Given that experience, I saw no reason to revisit his Goenka Lecture on YouTube. That is, until I came across Shashi Tharoor praising the speech on X. That shocked me.

Tharoor is no political novice. He is a four-term Member of Parliament. He has written widely on nationalism, history, diplomacy, and politics. For such a person to find Modi’s lecture “compelling” revealed either an astonishing lapse of judgment or a deliberate act of political repositioning.

Shashi Tharoor with Narendra Modi -A file photo

Lately, he has been discovering more virtues in the BJP than in the Congress. He has found it easier to laud Narendra Modi than to acknowledge Rahul Gandhi or Priyanka Gandhi—forgetting conveniently that he himself is a beneficiary of the very dynasty he criticises.

How else does one explain that the same Tharoor who went to Wayanad to campaign for Priyanka Gandhi now describes dynastic politics as a malaise? If she was dynastic, why campaign for her? Worse, he made his conciliatory remarks about Modi at a time when the Congress was fighting a tough election in Bihar. Was this inadvertent, or intentional?

Tharoor’s praise compelled me to listen to the lecture in full. It lived up to expectations—full of rhetoric, thin on substance, and wholly centred on himself. There was nothing—absolutely nothing—to praise. (That, in two sentences, is my review.)

Modi took credit for the NDA’s victory in Bihar, boasting that women voters had turned out in greater numbers than men. He said nine per cent more women had voted, and he portrayed this as evidence of “development.”

What kind of development was he referring to? In the span of seventeen days in July 2024, twelve bridges—big and small—collapsed in Bihar. If this is development, one shudders to imagine decay.

Let me explain what actually delivered Bihar to the BJP-led alliance. To do so, one must revisit a familiar story from Indian history—the Battle of Plassey. Students know that the British did not win because of superior weaponry alone. They won because Mir Jafar was bribed and turned traitor. Bribery, not gunpowder, secured their victory and, eventually, their empire.

Clive returned to England one of the richest men of his time. Those who returned wealthy from India were derisively called “Nabobs,” derived from our own word “Nawab.” Indian elections today bear an uncomfortable resemblance to those times. Elections have become less contests of ideas and more auctions of loyalty. Bihar’s recent election is a case in point.

When Modi visited Bihar soon after the Pahalgam terror killings, he did not meet victims. Instead, he told voters that their ballots would be a “reply to Pakistan.” But emotion alone cannot deliver 202 out of 243 seats.

Courtesy: South First

The real drama began with the Special Intensive Revision of the voter rolls. Instead of using the 2024 list as the base, the Election Commission revived the 2003 rolls. Seven million names disappeared. Four lakh new names appeared. The patterns raise troubling questions which the Commission has shown no interest in answering.

Meanwhile, the Commission waited patiently until all new welfare schemes were announced before allowing the Model Code of Conduct to take effect. And then came the masterstroke on 26 September: the launch of the Mukhyamantri Mahila Rozgar Yojana.

Under the scheme, 1.1 crore women were promised assistance between ₹10,000 and ₹2 lakh to start small businesses. Within days—days, not weeks—₹10,000 each had been transferred to 21 lakh women. This was the first instalment.

One must remember that ₹10,000 is not a trivial amount in Bihar, which has the lowest per capita income in India—₹32,227. To millions of women, this was a windfall, and behind every windfall lurks a fear: What if the government changes? Will this benefit disappear?

Is it then surprising that women voted in such large numbers? That nearly 80 percent turnout was recorded? That the ruling coalition swept the polls?

And this was just one scheme. Electricity bills were waived for two crore households consuming under 125 units. Social security pensions increased to ₹1,100 per month. Unemployed youths received ₹1,000 per month for two years. Every householder in Bihar became a beneficiary.

The BJP calls this a vote for development. But the NDA has ruled Bihar for most of the past twenty years. In those years, Bihar has remained at the bottom of every index—infant mortality, maternal health, literacy, women’s education, infrastructure. If this is development, one trembles at the alternative.

The Jan Suraaj Party has alleged that ₹14,000 crore of World Bank funds were diverted to finance these payments. If that accusation is even partly true, then India has just witnessed the world’s first election funded by international money. If elections become auctions, democracy becomes a commodity.

Shakespeare wrote in Julius Caesar that “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.” Bihar’s election forces us to ask uncomfortable questions. If the voting process itself is corrupted—through inducements, through manipulation of rolls, through strategic delays—what remains of democracy? If votes can be purchased, how long before democracy itself goes up for sale?

Against this disturbing backdrop, Modi’s Goenka Lecture displayed another familiar tendency: manipulating history for rhetorical gain. He went back 200 years to attack Thomas Babington Macaulay, quoting a fraudulent passage that has circulated widely but has no scholarly basis.

The fabricated quotation claims Macaulay travelled across India, found no beggars or thieves, admired India’s wealth and morality, and concluded that Britain must destroy India’s cultural backbone.

Thomas Babington Macaulay

There is no evidence—none—that Macaulay ever wrote or delivered such a statement. Scholars have debunked it repeatedly. It does not appear in his writings. He was in India when he supposedly said these words in the British Parliament. Also, the language used is modern, not the language found in the King James’ version of the Bible.

True, Macaulay’s Minute on Indian Education reflected a belief in European superiority. He was a colonial administrator, not a champion of Indian culture. His father was a missionary who instilled in him values which Modi, alas, cannot comprehend. But facts matter. Quotations matter. History matters. The Prime Minister of India has no right to quote fabricated history in a memorial lecture dedicated to a legendary newspaperman.

Modi also seemed unaware—or unwilling to acknowledge—what education in India was actually like before the British. Education was restricted to a few privileged castes. Lower castes and women were barred from reading Sanskrit texts. Ideas of universal schooling did not come from the Hindu social order. Missionaries, reformers, and colonial administrators played major roles in expanding education.

The world knew about the Vedas when Max Müller was commissioned by the British East India Company in 1847 to translate the Rigveda, a project that took 27 years to complete.One may critique their motives, but one cannot erase their contributions.

Macaulay also gave India the Indian Penal Code, still one of the least amended laws in the country. Amit Shah may have replaced it with a desi-sounding alternative, but as eminent lawyer Kapil Sibal remarked, it resembles the old IPC translated into Hindi using Google Translate—with the section numbers shuffled like a deck of cards.

What makes Tharoor’s praise more baffling is that he has himself been one of Modi’s sharpest critics. His book The Paradoxical Prime Minister is a sustained, detailed dissection of Modi’s political persona, administrative style, and ideological project. Hardly any praise for Modi is found in its pages. If anything, the book warns India about the dangers of blind hero worship.

And yet—here he was, applauding a speech that was factually incorrect, historically dubious, politically partisan, and rhetorically predictable.

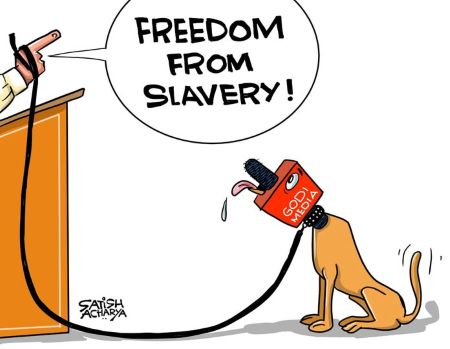

Modi used the Ramnath Goenka forum not to reflect on journalism but to attack the Congress—even its UPA ministries in which Tharoor himself served. He accused those governments of neglecting backward districts. He ignored facts. For instance, Goenka started his paper in English, not Tamil or Hindi. And Tharoor applauded him. Why?

Ambition? Realignment? A bid to remain politically relevant? Nobody outside Tharoor’s inner circle knows. But the symbolism is significant. When intellectuals begin echoing the powerful rather than questioning them, democracy loses one of its crucial checks.

Godi Media Lecture

The Bihar election has set a dangerous precedent in Indian politics. Vote-buying is no longer covert; it is institutionalised through state machinery. The Election Commission appears increasingly reluctant to play the role assigned to it by the Constitution. Welfare schemes are announced, implemented, and weaponised with breathtaking speed. Political campaigning is driven not by debate but by financial transfers.

The Bihar verdict was not a vote for development. It was a vote shaped by fear, inducement, manipulation, and a deluge of cash. Modi’s Ramnath Goenka Lecture, far from illuminating these issues, was another exercise in selective history and partisan chest-thumping. And yet, Shashi Tharoor applauded it—an act as puzzling as it is disappointing. Perhaps that is why the last words must go to Shakespeare, whose wisdom still resonates across centuries: “What’s past is prologue.”

Unless India reforms its electoral processes, reasserts the independence of its institutions, and restores the dignity of political debate, the future may look uncomfortably like the past—where power is purchased, not earned, and where truth is optional, not essential. For now, I can only say, with a sense of sorrow more than anger: Et tu, Tharoor? ![]()

Courtesy: Indian Currents

_________

Also Read:

Complaint Against Lawyers? Pay ₹6,500 First, Says Bar Council of Punjab & Haryana

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT