How the August Revolution inspired a vision of mass-led freedom — and how that vision was abandoned.

The Quit India Movement was not merely a chapter in India’s struggle for freedom — for Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia, it remained a defining moral and political compass long after independence. It shaped his convictions about people’s power, anti-imperialism, and the responsibilities of a free nation.

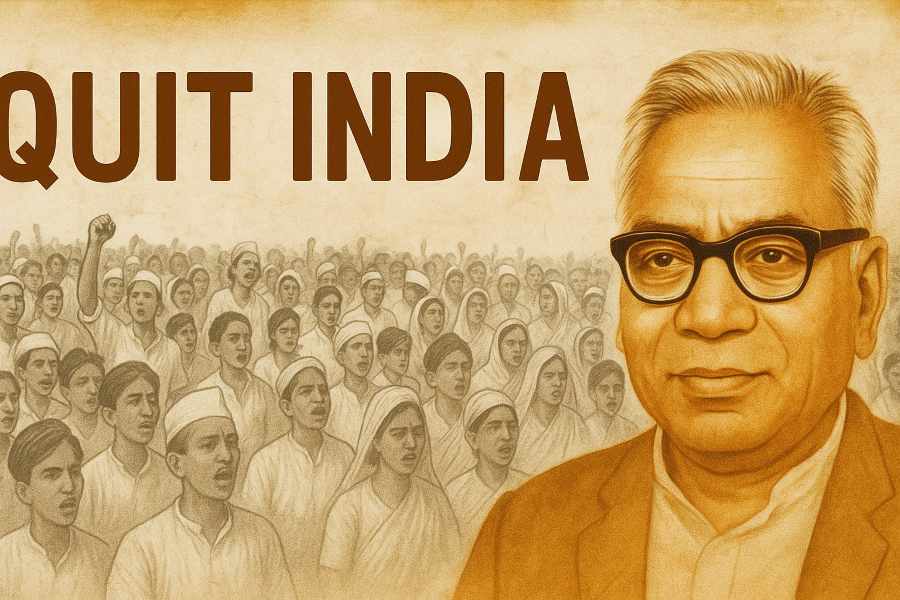

Ram Manohar Lohia

Lohia had worked underground for 21 months after the August 1942 call, constantly moving from place to place to evade arrest. On 10 May 1944, the British police finally caught him in Bombay. He was first imprisoned in Lahore Fort — notorious for its brutal interrogations — and later shifted to Agra jail.

He remained behind bars for two years. During that time, his father passed away, yet Lohia refused parole to perform the last rites. That decision was not merely an act of personal discipline; it reflected his refusal to accept any concession from an imperial power whose legitimacy he rejected.

On the 25th anniversary of Quit India, Lohia reflected on its meaning and its place in national memory. For him, 9 August was unlike any other date in India’s modern history:

“9th of August was and will always remain a people’s event.”

By contrast, 15 August, in his eyes, carried a different symbolism:

“15th August is celebrated with a lot of fanfare, for on that day the British Viceroy Lord Mountbatten shook hands with the Indian Prime Minister, and gave damaged independence to a damaged country.”

Independence Day 1947

If 15 August represented a formal transfer of power from one elite to another, 9 August represented something far deeper: the direct expression of people’s will — “we want to be free and we shall be free.” For the first time in centuries, crores of Indians had articulated and acted on that will, sometimes with overwhelming collective strength.

Lohia often compared India’s August Revolution with other global upheavals. Citing Leon Trotsky, he noted that in the Russian Revolution barely one percent of the population had participated, whereas in Quit India nearly 20 percent of Indians took part.

This difference, he argued, proved that Quit India was not simply a leader-led agitation; it was a movement in which ordinary people became their own leaders. It was, in that sense, one of history’s most profound experiments in self-activated mass politics.

His letter to Viceroy Linlithgow, written from Agra jail on 2 March 1946, remains a sharp articulation of that perspective.

In this letter, Lohia challenged the official British version of events. Linlithgow had accused the Congress leadership of plotting an armed uprising and claimed that those who joined the movement engaged in violent acts.

Quit India Movement

Lohia responded by cataloguing the crimes of British repression: indiscriminate firing on peaceful crowds, the torching of villages, mass arrests, and massacres so numerous and severe that he likened them to “many Jallianwala Baghs.”

Even in the face of such brutality, he insisted, the movement had remained essentially non-violent. Dismissing the Viceroy’s claim that fewer than a thousand people had died, he wrote:

“If we had planned an armed insurrection and our crowds were asked to resort to violence, believe me, Linlithgow, Gandhiji would today have been securing a reprieve for you from the free people and their government.”

For Lohia, the significance of 9 August was foundational:

“The history of the unarmed common man begins from the Indian Revolution of 9 August.”

The Second World War had brought new fractures into India’s anti-colonial camp. When Soviet Russia joined the Allied war effort, the Communist Party of India, following the Moscow line, opposed Quit India and instead declared support for Britain under the slogan of “People’s War.”

This choice sparked bitter confrontation between the Congress Socialists and the Marxists, and sowed confusion among many Marxist activists about what patriotism and sedition meant in the colonial context.

Ram Manohar Lohia

In the last months of his underground life, Lohia began drafting Economics After Marx. His biographer, Indumati Kelkar, describes the extreme conditions under which this work took shape: unstable shelter, constant police pursuit, worry about the movement’s fate, and a lack of access to key literature.

Despite these obstacles, she writes, the work became “a major contribution to the world on economics and to the views of the socialist movement,” offering an original and innovative interpretation of Marxian economics.

In this text, Lohia refrained from polemics against communists or other leaders who had opposed Quit India. Instead, he initiated a more fundamental rethinking of Marxism itself — a process that would continue into independent India and culminate, in part, in his 1952 Pachmarhi speech.

Reflecting on the wartime years, he recalled:

“In 1942–43 when the movement against the British was on, the socialists were either in jail or were being pursued by the police. That was also the time when communists, following their foreign masters, had given the slogan of ‘People’s War’. I was totally confused by the spectacle of Marxism in all its contradictions. Then I decided that I would discover the essential truth of Marxism and purge it from falsehood. Economics, politics, history and philosophy have been the four main facets of Marxism and I deemed it necessary to analyse all these. But as I was in the midst of analyzing its Economics I was arrested.”

From Lohia’s standpoint, Quit India was more than a nationalist uprising; it was the embryo of a government of free people, grounded in an enduring anti-imperialist will.

Yet, looking back 25 years later, he acknowledged its weakness:

“The will was short-lived, though strong. It didn’t have a lasting intensity. The day our nation acquires a tenacious will, we will be able to face the world.”

He believed that 9 August deserved to be celebrated with greater prominence, even imagining that its 50th anniversary might eclipse 15 August and 26 January in symbolic weight:

“26th January and 9th August are events of the same class. One expressed the will to freedom and the other the will to fight for it.”

Lohia never saw that 50th anniversary. It arrived in 1992 — a year that marked a deep betrayal of the spirit of 1942.

That year, India opened its economy to multinational corporate exploitation through the New Economic Policies, reversing decades of developmental self-reliance.

That year, India opened its economy to multinational corporate exploitation through the New Economic Policies, reversing decades of developmental self-reliance.

It was also the year of the demolition of a five-hundred-year-old mosque during the Ram Mandir Andolan, an event that deepened communal polarisation.

Since then, the nexus of neoliberalism and communal fascism has become entrenched, turning India’s ruling class into an adversary of the very people who had braved imperialist repression to win freedom in 1942.

Lohia’s reflections on the Quit India Movement — its unprecedented mass participation, its moral courage, and its vision of a genuinely free polity — remain urgent reminders of what was at stake, and of how far the republic has strayed from those ideals. ![]()

________

Also Read:

Noise Over Nuance: A Nation’s Debate in Decline

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT