A global surge in extreme wealth is redefining taxation, power and the future of democratic stability.

DEMOCRACIES HAVE SURVIVED wars, depressions and revolutions. Their most delicate test has always been inequality.

Every era that witnessed extreme concentration of wealth eventually faced a political reckoning. The industrial barons of the nineteenth century forced regulatory revolutions. Post-war Europe built welfare states not from charity, but from fear of imbalance. When wealth gathers too tightly at the summit, the pressure beneath it does not disappear. It accumulates.

We are living through another such moment.

In 1987, the world counted 140 billionaires. Today there are more than 3,000. Their combined wealth exceeds 14 trillion dollars, larger than the economic output of most nations. In the United States, billionaire wealth has more than doubled over the past decade. In Asia, fortunes have multiplied even faster. India alone now hosts more than 160 billionaires, placing it among the world’s largest billionaire clusters.

This is not ordinary prosperity. It is acceleration.

When prosperity rises, access often narrows.

Stock markets surge. Asset prices inflate. Digital monopolies entrench themselves. Meanwhile, wage growth for large segments of the population lags behind the expansion of capital. The divide between owning assets and earning income has widened into a structural fault line.

When fortune outpaces the republic, equilibrium shifts.

Democracy rests on political equality. Extreme wealth introduces economic asymmetry that quietly reshapes power. The ballot remains universal, but influence does not. Access narrows. Policy tilts. Regulation hesitates.

This is not a moral argument about envy. It is a structural inquiry into balance.

And balance, once disturbed at this scale, is not easily restored.

India’s Moment of Reckoning

India’s economic rise has been dramatic. Liberalisation, financial expansion and infrastructure growth have created extraordinary private fortunes. Ports, airports, telecom networks, digital platforms and energy corridors are increasingly controlled by a small constellation of corporate groups.

But the distribution of that wealth tells a harder story.

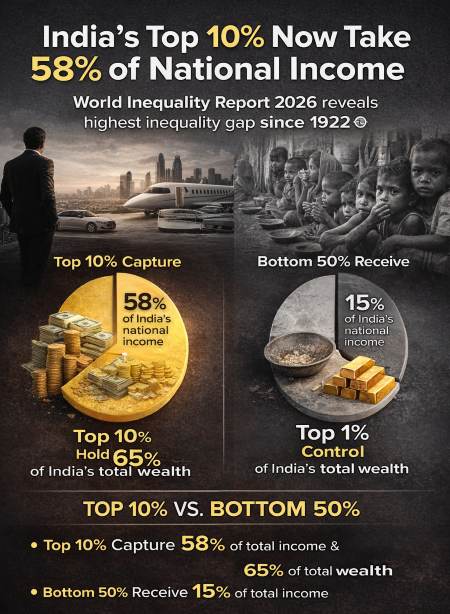

Recent inequality assessments indicate that the top one percent of Indians own more than 40 percent of the nation’s wealth. The bottom 50 percent together hold barely 3 percent.

GDP growth remains robust on paper, yet youth unemployment persists, informal labour dominates and rural incomes lag behind urban asset appreciation.

India abolished its wealth tax in 2015, citing limited revenue relative to administrative cost. The tax base remains narrow. Direct tax collections rely heavily on salaried professionals and corporate income, while indirect taxation forms a substantial share of revenue.

Capital gains structures continue to evolve, but the broader debate on taxing accumulated wealth has largely retreated from centre stage.

The paradox is stark. India seeks to become a five trillion dollar economy while half its population owns almost none of the wealth being created.

Growth without balance generates pressure. Pressure without policy generates fracture.

Pakistan and the Politics of Extraction

Across the border, Pakistan confronts a related dilemma under more fragile conditions. Its tax-to-GDP ratio hovers around 9 to 10 percent, among the lowest in South Asia.

The state depends heavily on indirect taxes that disproportionately burden ordinary consumers, while segments of elite wealth remain lightly taxed.

State Emblem Of Pakistan

At the same time, powerful industrial families, real estate magnates and politically connected conglomerates command significant economic leverage. Recurrent IMF negotiations underscore fiscal vulnerability. Debt servicing consumes public resources that could otherwise fund education, healthcare and infrastructure.

In such an environment, perceptions matter. When austerity is imposed on the public while privilege appears insulated, legitimacy weakens.

Inequality in fragile states is not merely economic. It is combustible.

A Tax Architecture from Another Era

Modern taxation systems were constructed in an industrial age. They were built for wages, profits and tangible assets. They assumed income would be declared, measurable and local.

Today’s ultra wealthy accumulate wealth differently. Appreciating shares, venture capital stakes, intellectual property rights and cross-border financial structures generate enormous asset growth without necessarily producing taxable income in a given year. Gains can remain unrealised for decades.

As a result, effective tax rates for some ultra high net worth individuals are often lower than those of middle-class professionals.

This is not necessarily illegality. It is structural lag.

Some governments are revisiting wealth taxes. Others are strengthening inheritance regimes or aligning capital gains more closely with income tax rates. Critics argue that wealth taxes historically faltered due to valuation complexity and avoidance. Supporters counter that digital transparency and global financial reporting make enforcement more viable today.

The deeper question is whether fiscal architecture can evolve at the pace of financial innovation.

When it does not, legitimacy erodes.

Capital Mobility Versus Democratic Stability

The most common warning against taxing extreme wealth is capital mobility. The wealthy can relocate, restructure or shift assets across jurisdictions.

Capital is mobile. But wealth is rarely rootless. It is embedded in ecosystems. Silicon Valley cannot be transplanted overnight. Nor can Mumbai’s financial networks or Karachi’s industrial base be replicated in exile. Markets, labour pools, legal systems and political stability form the soil in which fortunes grow.

Economic power increasingly converges at the top.

The greater danger may not be financial flight but democratic retreat.

When policymakers hesitate to reform for fear of unsettling concentrated wealth, they concede more than revenue. Economic power begins to shape political boundaries. Influence accumulates through lobbying, campaign financing and proximity to regulation.

Extreme wealth does not merely purchase assets. It purchases access.

And access reshapes policy.

The Question We Can No Longer Postpone

This is not a campaign against wealth. It is a confrontation with scale.

Democratic systems were built on the assumption that economic success would expand broadly enough to sustain political equality. That assumption is under strain. When asset ownership concentrates at the top while income growth below remains uneven, representation begins to feel abstract. The vote may be equal. Access is not.

Post-pandemic debt burdens are rising. Climate transition demands trillions in public investment. Young populations across South Asia demand opportunity, mobility and dignity. Financing these ambitions solely through indirect taxation and borrowing is neither equitable nor durable.

Post-pandemic debt burdens are rising. Climate transition demands trillions in public investment. Young populations across South Asia demand opportunity, mobility and dignity. Financing these ambitions solely through indirect taxation and borrowing is neither equitable nor durable.

Reform does not require confiscation. It requires recalibration. Stronger inheritance regimes, rationalised capital gains treatment, transparency in offshore holdings and smarter fiscal design may prove more effective than blunt instruments. The debate is not about punishing enterprise. It is about preserving equilibrium.

History offers no comfort to complacency. Republics rarely collapse in spectacle. They hollow slowly. Institutions remain standing while influence concentrates quietly behind them. Laws endure, but leverage shifts.

The billionaire era forces a decision that democracies can no longer defer.

If prosperity is private but stability is public, who bears responsibility for sustaining the republic?

That is not an ideological question. It is a constitutional one.

And constitutions, unlike markets, do not self-correct. ![]()

___________

Also Read:

Despite MSP, Punjab and Haryana Farmers Remain Deeply Indebted

Turban, Throne and Theatre: The Absurd Revival of Royal Rituals in a Democracy

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT