From Janus to Chardi Kala: Global and Spiritual Story of the New Year

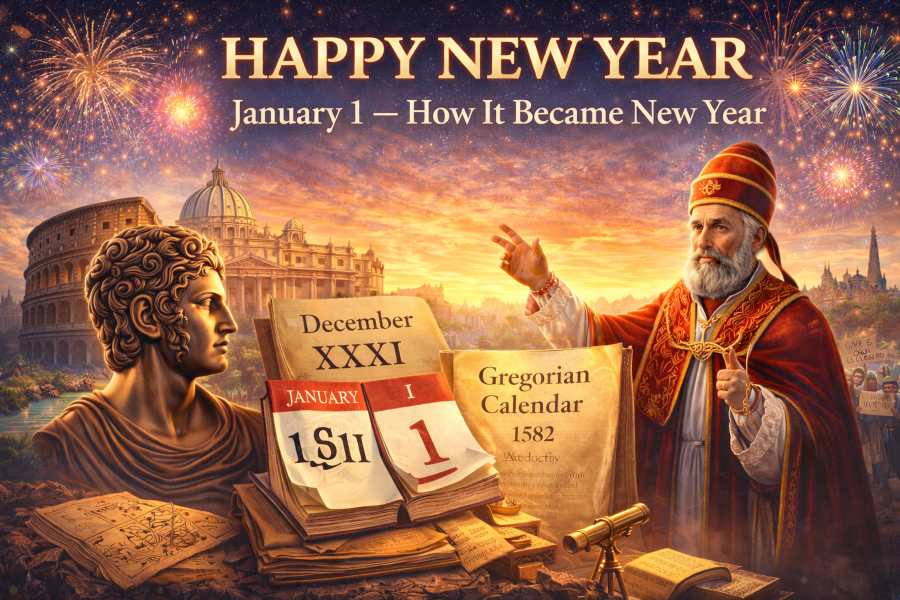

AS THE CLOCK strikes midnight on January 1, fireworks illuminate cities, families celebrate across continents, greetings flood messages worldwide, and humanity symbolically turns a fresh page. Yet why the world celebrates New Year on this day is no simple story.

It is a journey through Roman politics, Church debates, scientific corrections, psychological shock and, finally, global agreement.

Alongside this global calendar, India and Punjab continue to cherish their own powerful cultural ways of marking renewal — making the New Year both a shared human moment and a beautifully diverse experience.

From Janus to January 1 — How the World Got Its New Year

The idea of a “new year” has existed for thousands of years, but January 1 as New Year began in ancient Rome.

Rome’s legacy: January named after Janus, symbol of endings and new beginnings.

Early Romans once began their year in March, but Julius Caesar realised the calendar was chaotic and unreliable.

In 45 BCE, he introduced the Julian Calendar, realigning the year with the Sun and fixing it at 365 days with an extra leap day every four years. To symbolise renewed beginnings, he chose January — named after Janus, the Roman god of transitions, who had one face looking backward and one looking forward.

Romans celebrated January 1 with prayers, public festivities and hope for the future, much like the world celebrates today.

But although visionary for its time, the Julian system carried a tiny flaw: it miscalculated the solar year by about eleven minutes annually.

The mistake seemed insignificant, yet over centuries it pushed the calendar off track. Seasons drifted, religious dates shifted, and eventually Easter and other major festivals no longer aligned with the natural world. Time itself seemed to slide.

The Mystery of the Missing Eleven Days

By the 16th century, the error had grown too large to ignore. To restore order, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian Calendar in 1582, realigning dates with the solar cycle. Beyond simply correcting the drift, he added a crucial scientific refinement to the leap year system: century years would only be leap years if they were divisible by 400.

1752: Britain wakes up eleven days ahead — sparking protests and confusion.

That is why 1900 was not a leap year, while the year 2000 was. This precision corrected the eleven-minute annual miscalculation and firmly restored January 1 as the recognised New Year.

However, adopting this correction was not as simple as printing a new calendar. To erase centuries of accumulated error, countries had to delete days altogether. Clocks did not stop, but calendars jumped forward.

The number of “lost” days depended on when each nation embraced the reform. While early adopters in 1582 removed ten days, by the time Britain and its colonies finally switched in 1752, the loss had risen to eleven.

People went to bed on 2 September and woke up on 14 September.

It became one of history’s strangest human experiences. Many felt as though days of their lives had been stolen. Rumours spread that wages would be unpaid, rents unfairly calculated, festivals lost and prayers invalidated.

When time jumped forward: the world adjusts to the corrected calendar.

Historical references even speak of protests demanding, “Give us our eleven days!”

Doctors worried about medical records, lawyers questioned legal validity, priests debated religious observances. Governments had to reassure citizens that nothing in life had changed — only the mathematics of timekeeping.

For the first time, societies collectively understood something profound: calendars are not divine truths, but human decisions. Time is both scientific measurement and emotional experience. Yet humanity adapted.

The reform brought stability, restored seasonal accuracy and created the shared international system of time — and the global New Year — we recognise today.

India’s Many New Years — A Civilisation of Time and Spirit

While the Gregorian calendar binds the modern world together, India tells a deeper civilisational story of time. Here, calendars were never merely tools of measurement; they aligned human life with nature, seasons, astronomy, spirituality and cultural identity.

The Vikram Samvat calendar, historically used across much of North India, traditionally marks New Year around spring.

Also Read: Celebrating a South Indian Tradition Across the Globe

The Shaka Calendar, later adopted officially as India’s National Calendar, follows a solar framework and continues to influence civil and cultural life.

India celebrates many New Years — each rooted in culture, faith and seasonal rhythm.

Across India, New Year does not arrive on one universal date but unfolds through the year — from Ugadi in the Deccan and Gudi Padwa in Maharashtra to Navreh in Kashmir, Cheti Chand in the Sindhi tradition, Poila Boishakh in Bengal, Vishu in Kerala and Puthandu in Tamil Nadu.

In Punjab, Baisakhi marks both harvest joy and the historic creation of the Khalsa, symbolising courage, identity and spiritual renewal.

The Nanakshahi Calendar further provides clarity and structure to Sikh observances, placing faith, history and remembrance meaningfully within time.

Together, these celebrations remind us that while January 1 unites the world, India’s cultural soul honours renewal many times a year, each moment deeply meaningful and spiritually alive.

From Celebration to Chardi Kala — The Deeper Meaning of Renewal

Today, January 1 is not merely a date; it is a global pause — a moment when humanity collectively breathes, reflects and hopes. It is celebrated in streets and living rooms, on television and social media, in silence and in song. The world may be divided by geography, language, culture and politics, yet New Year remains one of the few truly shared human experiences.

Chardi Kala — a spirit of optimism, courage and collective wellbeing.

Beyond fireworks and festivities lies a deeper message, one that resonates strongly with Punjab’s cultural soul. The essence of renewal is not simply celebration; it is resilience. It is confidence in the face of uncertainty. It is the belief that even when life tests us, we do not surrender our dignity or spirit.

The Sikh ideal of Chardi Kala expresses this beautifully. Chardi Kala is not about ignoring pain; it is about refusing to be defeated by it. It is not naïve optimism; it is disciplined courage.

Chardi Kala is the strength to smile through hardship, the will to stand upright when storms rage and the quiet conviction that the human spirit cannot be broken by circumstance. Linked with the profound principle of Sarbat da Bhala, it reminds us that renewal is not merely personal; it is collective. We rise, but we wish and work for everyone to rise.

Thus, as January 1 dawns, may we not simply mark another date, but renew our resolve to pursue truth, justice, compassion and courage.

Also Read: Breaking Barriers: Guru Nanak’s Teachings and Travels

May we step into the future with clarity, responsibility and confidence — not just wishing for a better year, but working towards one with intent and integrity.

May this New Year be our strongest yet.![]()

________

Also Read:

SAHITYA AKADEMI AWARDS ROW: Power Comes A-Knocking, or Writers Go Knocking at Power’s Door?

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT